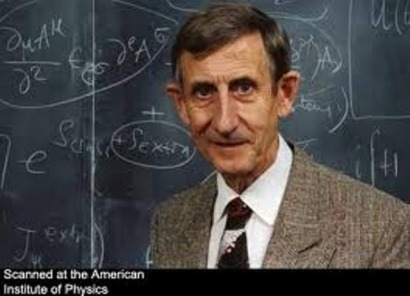

Long renowned for his work in quantum field theory, mathematics, physics, astronomy and nuclear engineering, the British-born octogenarian has in recent years been almost as well known as an unrepentant critic of the current state of climate change science.

For the most part, Dyson, who even friends have described as “subversive” (while in the same breathe describing him as one of the most original thinkers of our time), debunks the science while describing the hand-wringing over it unnecessary.

But more on that subject later.

Far more important for our purposes was his current thinking on renewable energy, a topic he’s written on sporadically since 1960, when he first imagined, in the pages of the journal Science, the creation of what came to be known as “Dyson spheres”.

Put simply, his theory was that a technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilization might completely surround its native star with artificial structures in order to maximize the capture of the star’s available energy.

More recently, in his 1999 book The Sun, the Genome, and the Internet, he described a vision of clean energy and green technology enriching villages around the globe; Dyson’s notion was that this new world order would be powered by sunlight captured by plants that were genetically engineered to convert the light into chemical fuels.

During a recent conversation with Renewable Energy Magazine, Dyson said he’s still an advocate for solar power, but added that “it all depends on what time scale you are talking about”.

“I mean, I think in centuries, whereas most people think in decades, and that makes a huge difference,” he said from the office he continues to maintain at the Institute of Advanced Studies, an extraordinary bastion of scholarship tucked into a tree-lined residential neighborhood in Princeton, NJ in the US.

“So I would say for the next few decades, I don’t think solar energy is that important,” he continued. “But if you talk about a couple of centuries from now, yes. And I think it’s important to keep that distinction.”

Dyson went on to explain that his timeline is dependent on several factors.

“I would say the first is the science,” he said. “We haven’t yet done the science to know how to use solar energy cheaply. It’s not just about development [of the technology]. A lot of science still needs to be done, especially around the whole notion of really using biology to efficiently replace chemical industries. There’s just no way to do that with our existing knowledge. So that’s what I mean by thinking in centuries. Science takes a long time. Science is slow.”

“And it may get there in 50 years, or maybe 100, we just don’t know,” he added.

The other factor Dyson pointed to was simple economics. In that regard, he said the big change in the last 10 years is that we now know that there is far more natural gas available than was originally believed.

“As a result, the economics of energy has changed quite drastically,” he said. “It’s going to be a lot cheaper to use natural gas, and that’s certainly good for the next 50 years. I mean, the fact is, that natural gas has enormous advantages. We switched from oil to natural gas in my home 20 years ago and that turned out to be a wise move.

“Natural gas is cleaner and cheaper and more reliable, and it doesn’t need to be imported,” he continued. “So that means there’s no hurry about going to sustainable energy, and now we’ve found out, because of this cracking process, that [natural gas] is actually much more abundant than we thought.”

Ever the contrarian, Dyson went so far as to suggest the current generation of renewable energy technologies is merely “a toy for the rich.”

Pressed on that, the physicist refused to relent, but amended his assessment by saying, “there’s nothing wrong with that.”

“But that said, we need to recognize that they are not solving the real problem. There’s nothing [out] there right now that’s actually cheap enough to be useful for the world as a whole.”

Nuclear dreams

Not surprisingly, given his extensive work on the Orion Project, a five year effort in the late 1950s and early 1960s to explore the possibility of space-flight using nuclear pulse propulsion, Dyson is far less reserved about to potential of nuclear power.

“It’s good because we do know how to do it,” he said. “It’s a useful resource. But of course, at the moment, it’s still expensive. It’s not quite clear why it’s so expensive – whether it’s because of the lawyers or some other, natural reason – but I tend to believe it’s the former. The lawyers have had a fine time with making nuclear energy expensive.”

Dyson seemed bemused by his own comment, evidently finding banging on attorneys, however gently, quite satisfying. That didn’t mean, however, that he doesn’t believe politicians are equally guilty of getting in the way of scientists and technologist.

Dyson recalled his work, in 1958, as leader of the design team for the TRIGA, a small, inherently safe nuclear reactor used by hospitals and universities the world over for the production of isotopes.

“When I started as a nuclear engineer 50 years ago, we designed a reactor and built it and licensed it and sold it, all within two years. And that’s the way it should be,” he said. “Now it takes 20 if you are lucky [laughs]. So obviously, there’s been a theory of slowing down.”

But if nuclear power has been an object of derision and fear in the US since the accidental partial core meltdown in 1979 at the Three Mile Island Generating Station south of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the technology has enjoyed far more acceptance in Europe, particularly in France.

“In France, where things are different, nuclear energy has done pretty well,” Dyson said. “They haven’t had any big problems; they just went ahead and did it. So they now have, by far, the most successful nuclear industry in the world and they are happy with that and will continue to pursue it. France demonstrates that you can do it if you want to.”

But that’s not say Dyson, who became a naturalized US citizen in the late 1950s, believes America has lost its edge.

“I would say that’s partly true, but the fact is other countries are getting much further ahead of where they were because of the fact they’ve had peace and quiet for the past 50 years,” he said. “I mean, Europe being at peace for 50 years has made a big difference. Europe can now afford to do things that they couldn’t do before; for instance, as I say that, I’m thinking specifically of the European Southern Observatory, which is now the best observatory in the world for ground-based astronomy. That’s no accident. The Europeans decided to do that and they’ve done extremely well.”

Of course, one doesn’t get so far in US by pointing out how the French or anyone else does something better, a reality Dyson readily acknowledged.

“We hate to be told we have something to learn,” he said.

He nevertheless believes “hard experience” will break down that intransigence, in terms of nuclear, and the renewable energy sector as well.

“I mean, when the Chinese really are going ahead and we are behind, I think we’ll change our habits,” he said.

The climate controversy

As Dyson speaks, he often quickly follows a definitive-sounding statement with a slight hedging of his bets.

More often than not, these come in the form of, “Of course, we don’t know that for sure. But I believe it’s likely.”

“If you look at almost anything in the world around you, you find out we really don’t understand it,” he said at another point.

And that, in a sense, sums up his departure from the orthodoxy when it comes to the subjects of climate change and global warming.

Dyson began publicly expressing his reservations about the conventional wisdom on climate change in 2005, the year he told a Boston University audience in his inimitable style that “all the fuss about global warming is grossly exaggerated”.

A critic of both Al Gore, whom he has described as climate change’s “chief propagandist” and James Hansen, head of NASA’s Goodard Institute for Space Studies in New York, who, he says relies too heavily on computer-generated models to form his dire climate assessments, Dyson has said the mistake both are making is focusing on one aspect of climate science, while failing to include the biology and chemistry of the planet’s natural systems in the deliberations.

Dyson has even gone so far as to suggest the escalating amount of carbon in the atmosphere may actually be beneficial because carbon is an ideal fertilizer for the planet’s food stocks.

While his critics charge that Dyson himself isn’t exactly steeped in contemporary climate science, a perusal of his long and varied resume does lend some credibility to his position.

Back in mid- to late-1970s, Dyson worked with a pioneering, multidisciplinary team on climate issues at the Institute for Energy Analysis in Oakridge, Tennessee; around the same time, he also worked on climate studies conducted by the JASON, an independent group of scientists that advises the US government on science and technology issues.

“This was analysis, not development. They were not developing systems, but simply analyzing the natural processes,” Dyson said. “What was really good about [the Institute for Energy Analysis] was a man named Jim Schlesinger, who’s still in the game, serving as president the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies [an independent research organization in Millbrook, NY].

“Schlesinger, whose specialty is biogeochemistry, understands that topsoil, which is sort of the second biggest reservoir of carbon in the world, is strongly coupled to the atmosphere; so during that period he did a lot of interesting experiments on the exchange of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the soil. It was worked geared toward looking at natural processes and understanding how carbon dioxide travels through the biosphere, not just the atmosphere.”

As for his contention that the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere may in fact be a good thing, Dyson said he’s been saying much the same thing for “almost 30 years”.

“What I’ve been saying is the biological effects of carbon dioxide are at least as important as the climate effects,” he said.

While working with the Institute for Energy Analysis, Dyson penned a 1976 paper entitled Can We Control The Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere? In it he argued that the carbon dioxide generated by burning fossil fuels could theoretically be controlled by growing huge numbers of trees as a kind of planned carbon-offset forestry program.

Thirty-five years later, he stands by the theory.

“Roughly speaking, what I was saying is all you needed to do is plant a trillion trees and that would do the job [of eliminating excess carbon from the atmosphere],” Dyson said. “And I think that’s still true. If anything has changed, I think it’s that there are now many other kinds of land management which would also be just as good.

“Anything you can do that puts carbon into the soil is essentially like growing trees,” he continued. “It’s the same thing. So you don’t have to plant a trillion trees; you can also grow a foot of topsoil over a big area and that would be just as good from the point of view of the atmosphere.”

“Certainly, there are a lot of possibilities there and it has not been studied thoroughly enough,” Dyson said, momentarily raising his normally soft-spoken voice. “I’m amazed at how little we’ve learned in the last 30 years. People have not done much in terms of large scale monitoring of soil and measuring carbon fluxes and this kind of thing”

As to why no one has ever done the ongoing research in the area, Dyson said it all boils down to money, and a political squabble between researchers at the Institute for Energy Analysis, who were stressing biology, and those at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, who were stressing weather and climate in their work.

“At the time, 90 percent of the money going into this research was being spent on climate modeling and 10 percent was being spent on studying the real world,” Dyson said.

“That’s a ration that has more or less continued ever since,” he added. “The people who are doing the climate modeling somehow or another have always gotten the bigger share.”

Try all the renewables you can

Returning to the subject of renewable energy, Dyson said, “I think we should try everything. Nobody knows what works. That’s true of any technology”.

“The things that work are often very spectacularly better than the competition, but nobody knows why,” he continued. “It’s like with the bicycle. We still don’t really understand why a bicycle is so good. In fact, I was reading a paper just the other day about that.

“There were hundreds and hundreds of designs of bicycles and most of them were complete failures,” he said. “It wasn’t done by a rationale process. It was just essentially Darwinian evolution. And I think the same is true of most technologies: that if you try out 100 different things, you find one or two of them are really good, but you don’t really know why.”

One reason Dyson has been so critical of those who have drawn so much attention to climate change is the spotlight it takes away from other grinding issues, such as poverty in the developing world.

Asked how he’d strike a balance between the need to develop non-carbon based sources of power and bringing prosperity to the developing world, Dyson responded by saying you should do both.

That led to a discussion of the Central African nation of Rwanda, where efforts are currently under way to deploy solar power to electrify 300 rural schools. Among those involved in the effort is a Dyson friend, Bob Freling, executive director of the Solar Electric Light Fund.

“He electrifies villages and schools and he’s been working in Rwanda and other place, and while he’s very successful and knows what can be done, it’s essentially, again, toys for the rich in a way,” Dyson said.

“I mean, you electrify a school and the children there have a wonderful time. They get internet connections and they join the modern world and they can get jobs on the city; it’s a great thing for the village,” he continued. “But it really, at the moment, depends on funds from the outside and it’s very small scale. The schools get a few kilowatts, which is fine, but what the world needs, of course, is gigawatts, not kilowatts – roughly a million times more.

“So what I’m saying, is you need both,” he said. “Certainly it’s great to put a small amount of kilowatts into villages. It’s a great idea. But if you really want to modernize a country, you want something more, which is a centralized power system. So we should go ahead with both, as fast as we can.”

A good place to work

Dyson and his wife Imme live quietly in Princeton in the same home he’s resided in since 1953. The couple was married in 1958. He was previously married to mathematician Verena Huber-Dyson, and between the two marriages is the father of six children.

His eldest daughter is Esther Dyson, the noted digital technology consultant. His son is scientific historian George Dyson.

These days, even in retirement -- and even when the forecast called for a mix of sleet and snow as it did on the day of this interview -- he still walks to the office he keeps at the Institute of Advanced Studies, a place he’s long referred to as “a motel with a stipend” due to the ever-changing number of scholars who set up shop there for periods generally lasting from one to three years.

Years ago, Albert Einstein, who died two years after Dyson’s arrival, also made it a daily practice to walk to work at the Institute. And for many years, Dyson’s next door neighbor was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who as technical director of the top secret Manhattan Project oversaw the US creation of the atomic bomb.

Among those who Dyson is currently likely to encounter over the course of his day is Edward Witten, a leading researcher into superstring theory, whose office at the institute is directly across the hall from his own.

Asked why he grew so attached to the institute, Dyson said the main reason is “it’s a good place to work and it’s an international meeting ground.”

“People come from all over the world, essentially just to get to know each other and find out what the interesting problems are to work on, and then, with luck, they go home and actually do something,” he said.

As for himself, Dyson says that even at 87, there are no shortage of scientific questions to ask and explore.

“When you talk about renewable energy, of course, the basic question is, how does the genetic apparatus actually work? We’re at a point where it’s become much cheaper to collect genomes, so we have this big database of genomes, a wonderful amount of information, but nobody really has the foggiest idea what it means [laughs]. We don’t know the language. We can decipher proteins, we can decipher a certain amount of RNA, but that’s about it. We just don’t understand the basic architecture of the genome.

“I think that’s sort of problem number one,” he said. “If you want to be design creatures to do what you want them to do in an efficient and sustainable way, you want to really be able to speak the language of the genome. That’s something we don’t know how to do, but when we do, I think it will make a huge difference.”

For renewable energy?

“Yes. For whatever you like,” Dyson said. “For example, if you want to extract chemicals from the ground, instead of digging mines, you could design a little turtle which could dig into the ground, eat the stuff, concentrate it, and bring it to the surface. It would be a much cleaner and more sustainable way of doing it.”

With so many ideas, it seemed somehow natural to wonder whether Dyson sometimes misses the minds of the past that he could bounce his ideas off. While one might have been tempted to think of Oppenheimer, considering the close proximity in which they lived, Dyson extinguished the idea by describing Oppenheimer as “a special case”.

“He didn’t do very much of that kind of thing. He was, in a strange way, very narrow in his interests,” Dyson continued. “I suppose the first person I would be most happy to have around would be John von Neumann.”

Neumann, a Hungarian American mathematician who died in 1957, built his reputation in Princeton and around the world with the major contributions he made to set theory, functional analysis, quantum mechanics and economic and game theory, and through his gregarious personality.

“[Neumann] thought at lot about exactly this kind of problem, and believed in weather control; in fact, that’s why he built his first computer, the first computer we ever had here at the institute,” Dyson said. “He broke all the rules by bringing engineers here. Really, he was a delightful character to have around. I miss him very seriously.

“Another would be Jule Charney, the meteorologist,” he continued. “He was a friend of von Neumann’s and I used to talk to him a lot. I mean, [decades ago] he was already designing schemes to make the Sahara green and that kind of stuff.”

Dyson admitted to sometimes wondering about the fickle fate of such ideas, but said he was never particularly frustrated at having come up with a concept or theory that wasn’t follow-up by somebody else.

“Because there are always 100 new problems to think about,” he explained. “If something doesn’t attract attention, you just forget about it and do something else.”

Although he now spends much of his time thinking about astronomy and biology, Dyson said he’s not really doing science anymore.

“I’m mostly just writing book reviews and giving speeches and talks and generally being an elder statesman. I don’t pretend to compete with the younger people,” he said, and he professed to be perfectly content.

“Oh yes. I’m quite happy,” Dyson said. “I mean, obviously, the young people in some ways have more fun, but on the other hand, they have problems too. They have to look for jobs [laughs].”

For additional information: