The definition of a battery is a device that generates electricity via reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction and also stores chemical energy (Blanc et al., 2010). This stored energy is used as power in technological applications. Flow batteries (FBs) are a type of batteries that generate electricity by a redox reaction between metal ions such as vanadium ions dissolved in the electrolytes (Blanc et al., 2010). VRFBs are aqueous-based RFBs. They have vanadium in different oxidative states as the electrolyte. These vanadium species undergo oxidation-reduction reactions to produce energy. VFRBs were characterized by Skillas-Kazacos et al. (1987).

This study specifically characterized the performance of VFRB using V2+/V3+ and V4+/V5+ for the negative and positive half cells, respectively. The negative and the positive half cells were supplied with the vanadium electrolytes from the anolyte and the catholyte, respectively. The set-up also used carbon felt electrodes and polystyrene sulfonic acid cation selective membrane. The study reported a voltage efficiency of 81% that was calculated over a range of 10-90% state-of-charge.

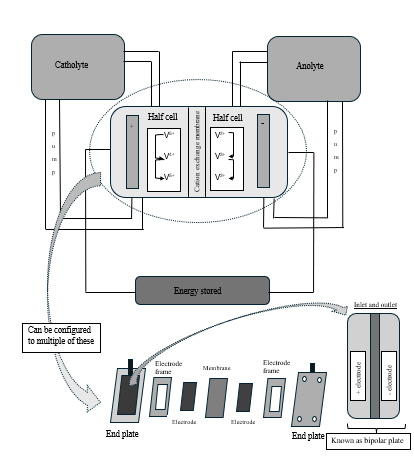

Figure 1 outlines the basic configuration and operation principles of the conventional VRFB. The two electrolyte tanks, namely a catholyte and an anolyte, have vanadium species. These could be V4+ and V5+ in the catholyte and V2+ and V3+ in the analyte (Barzigar et al., 2025). These electrolyte tanks are connected to a central cell that has a cation exchange membrane in the middle. It is in the cell where oxidation and reduction reaction cycles involving vanadium species occur. In the part of the cell connected to the catholyte, referred to as the half-cell, V5+ ions are reduced to V4+ ions and these are oxidized back to V5+ ions. In the other half cell connected to the anolyte, V2+ ions are oxidized to V3+ ions and these are reduced to V2+ ions. The two half cells are separated by a membrane and in some cases, this could be a cation exchange membrane.

Figure 1: Basic schematic diagram of a single cell vanadium redox flow battery

The setup including the cell could be configured depending on the VRFB application. This includes the use of pumps in the setup connecting the catholyte and the anolyte to the half-cells to control the flow of the vanadium species (Cunha et al., 2015).

The half-cells are connected to an energy storage unit as in Figure 1. When observed from the outside, the whole set-up is in the form of a stack with the membrane and the electrode stacked in an electrode frame which in turn is against an end plate. There is a current collector inside the end plate which is connected to a bipolar plate. It is on the bipolar plate where the catholyte and anolyte flow occurs as shown in Figure 1 to generate a VRFB electrical flow field. The stack is a core component of the VRFB because not only does it provide a site for the electrochemical reaction to occur but it is also the site where chemical energy is converted to electrical energy (Huang et al., 2022).

The different types of VRFBs

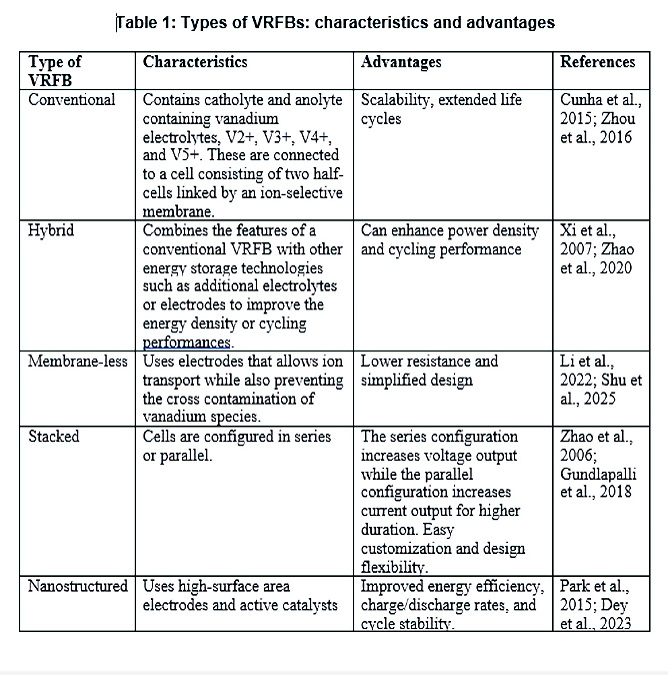

There are five different types of VRFBs: conventional, hybrid, membrane-less, stacked, and nanostructured VRFBs. They all have different characteristics and they all have advantages. While the conventional VRFBs have advantages in scalability and extended life cycles (Cunha et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016), the hybrid VRFBs have the ability for enhanced power density and cycling performance (Xi et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2020). The membrane-less VRFBs have lower resistance and a simplified design (Li et al., 2022; Shu et al., 2025) compared to the other types of VRFBs.

The series arrangement in the stacked VRFBs increases voltage output while the parallel set-up increases current output for higher duration (Zhao et al., 2006; Gundlapalli et al., 2018). Nanostructured VRFBs are relatively new and have shown promises for improved energy, charge-discharge rate, and cycle stability (Park et al., 2015; Dey et al., 2023).

In the next segment

VRFBs have been studied for their application as a power source for wind farms (Lei et al., 2017), semiconductor plants (Shigematsu et al., 2002), and wind turbines (Mena et al., 2017). In our next segment on VRFBs, we will discuss their applications in wastewater treatment that will shed light on the effectiveness of this energy technology that albeit with a complex structure is so simple in producing energy. As we will see, there is success and there is also challenges in these applications.

References

Agarwal, H., Roy, E., Singh, N., Klusener, P. A. A., Stephens, R. M., & Zhou, Q. T. (2024) Electrode treatments for redox flow batteries: translating our understanding from vanadium to aqueous-organic, Advanced Science, 11(1), 2307209. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202307209

Barzigar, A., Ebadati, E., Mujumdar, A. S., & Hosseinalipour, S. M. (2025) A comprehensive review of vanadium redox flow batteries: Principles, benefits, and applications. Next Research, 2(4), 100767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexres.2025.100767

Blanc, C., & Rufer, A. (2010) Chapter 18: Understanding the vanadium redox flow batteries https://doi.org/10.5772/13338, In Paths to Sustainable Energy, Intech Open, London. UK.

carbon nanotubes, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 125(2), 1234-1239. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c09058

Cunha, A. C., Martins, J., Rodrigues, N., & Brito, F. P. (2014) Vanadium redox flow batteries: a technology review. International Journal of Energy Research, 39, 889-918. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.3260

Dey, G., Saifi, S., Sharma, H., Kumar, M., & Aijaz, A. (2023) Carbon nanofibers coated with MOF-derived carbon nanostructures for vanadium redox flow batteries with enhanced electrochemical activity and power density, ACS Applied Nano Materials, 6(10), 8192-8201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.3c00347

Gundlapalli, R., Kumar, S., & Jayanti, S. (2018) Stack design considerations for vanadium redox flow battery, Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering, 3, 149-157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41403-018-0044-1

Huang, R., Liu, S., He, Z., Zhu, W., Ye, G., Su, Y., Deng, W., & Wang, J. (2022) Electron-Deficient Sites for Improving V2+/V3+ Redox Kinetics in Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries, Advanced Functional Materials, 32, 211661. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202111661

Lei, J., & Gong, Q. (2017) Operating strategy and optimal allocation of large-scale VRB energy storage system inactive distribution networks for solar/wind power applications, IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution, 11(9), 2403-2411. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2016.2076

Li, X., Qin, Z., Deng, Y., & Wu, Z. (2022) Development and challenges of biphasic membrane-less redox batteries, Advanced Science, 9(17), 2105468. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202105468

Mena, E., Lopez-Vizcaino, R., Millan, M., Canizares, P., Lobato, J. & Rodrigo, M. A. (2017) Vanadium redox flow batteries for the storage of electricity produced in wind turbines, International Journal of Energy Research, 42, 720-730. https://doi.org/10.1002/er.3858

Park, M., Ryu, J., & Cho, J. (2015) Nanostructured electrocatalysts for all-vanadium redox flow batteries, Chemistry - An Asian Journal, 10(10), 2096-2110. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201500238

Shigematsu, T., Kumamoto, Deguchi, H., & Hara, T. (2002) Applications of a vanadium redox-flow battery to maintain power quality, IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exhibition, Japan. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDC.2002.1177625

Shu, Y., Xiao, H., Yu, Y., Yu, Z., Lin, Y., Sun, Y., & Huang, J. (2025) Toward membrane-free flow batteries, ACS Applied Energy Materials, 8(13), 8710-8725. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.5c00799

Skyllas-Kazacos, M. & Grossmith, F. (1987) Efficient vanadium redox flow cell. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 134 (12), 2950-2953. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2100321

Xi, J., Wu, Z., Qiu, X., & Chen, L. (2007) Nafion/SiO2 hybrid membrane for vanadium redox flow battery, Journal of Power Sources, 166(2), 531-536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.01.069

Zhao, P., Zhang, H., Zhou, H., Chen, J., Gao, S., & Yi, B. (2006) Characteristics and performance of 10 kW class all-vanadium redox-flow battery stack, Journal of Power Sources, 2(22), 1416-1420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.08.016

Zhao, X., Kim, Y.-B., & Jung, S. (2023) Shunt current analysis of vanadium redox flow battery system with multi-stack connections, Journal of Energy Storage, 73, 109233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.109233

Zhou, X. L., Zhao, T. S., An, L., Zeng, Y. K. & Zhu, X. B. (2016) Performance of a vanadium redox flow battery with a VANADion membrane, Applied Energy, 180(15), 353-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.08.001