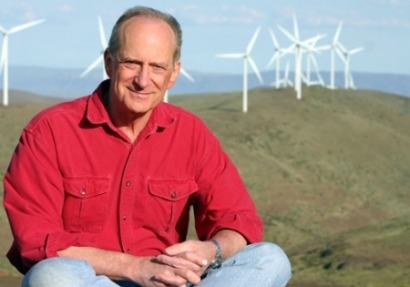

Denis Hayes was coordinator for the first Earth Day in 1970 and first head of the US Solar Energy Research Institute (now known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory). He currently heads up the Bullitt Foundation, the mission of which is "to safeguard the natural environment by promoting responsible human activities and sustainable communities in the Pacific Northwest".

“There are those [in the US] who think that renewable energy is somehow “liberal” energy or something; but the sector is pretty strongly imbued with the entrepreneurial spirit, it’s involved in decreasing our reliance on fragile imported sources of oil, and it’s achieved a high degree of support from many of the US military services.... I mean, there’s a whole bunch of rationales [for supporting renewable energy] that with the right packaging and the right spokespeople could perhaps be persuasive across the political spectrum.”

With the banging of a gavel on a Wednesday afternoon in January in Washington, DC, a new Congress came to power in the United States and, if advocates for climate change legislation are correct, the prospects dimmed markedly for a new US policy on carbon emissions reductions. That sense of hope lost, however, did not extend to renewables, where the consensus of opinion seems to have formed around uncertainty. Yes, the outgoing Congress extended incentives for solar, wind and other renewables last year, but it’s entirely unclear whether those incentives will survive when they again come up for consideration about 12 months from now.

The current package of incentives allows solar and wind power facilities to obtain federal grants equal to a tax credit worth 30 percent of the cost of building a new facility and continues support for the ethanol industry.

But some conservatives – the segment of the Republican Party now in the driver’s seat in the US House of Representative -- opposed the extension because it could add to the federal deficit, and they’ve suggested that renewable energy projects should not rely on government support in the future.

Among those with a meaningful perspective on what may happen is Denis Hayes, who rose to prominence in the US as the coordinator for the first Earth Day in 1970 and was appointed head of the US Solar Energy Research Institute (now known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) by then President Jimmy Carter.

Hayes left the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in the US after being selected by US Senator Gaylord Nelson to organize the first Earth Day. Held on April 22, 1970, the event had participants in two thousand colleges and universities and hundreds of communities across the US In 2010, the annual observance is believed to have included more than 20 million people around the world.

Following the success of the first Earth Day, Hayes founded the Earth Day Network, an organization for which he serves as chairman of the board.

During the Carter Administration, he not only oversaw the fostering of solar energy as a viable resource, he and his staff actually came up with a comprehensive plan to have a fifth of the power used in the United States supplied by solar energy by the year 2000 – a plan that died when Carter lost his bid for re-election to Ronald Reagan in 1980.

He also oversaw the Administration’s efforts to promote the wind energy sector. Hayes left government after the Reagan administration cut funding for the agency. Since 1992, Hayes has been president of the Bullitt Foundation in Seattle, Washington in the US and continues to be an outspoken leader for renewable energy and environmental policy, and has been tireless in his efforts to make America’s Pacific Northwest a global model for sustainable development.

Interview date: January 2011

Interviewer: Dan McCue

As we entered the new year, and especially with the change in control of Congress, it seems that we have entered a period of uncertainty when it comes to federal activity on the renewable energy and carbon emission reduction fronts. Do you feel that way?

Oh, it would be pretty difficult to view federal policy on anything that effects carbon emissions optimistically, given the articulated views of the leadership and the rank and file of the party now in control of the US House of Representatives. However, I don’t know that necessarily carries over to renewable energy.

There is some scepticism in some quarters. There are thouse who think that this is somehow "liberal" energy or something; but at the same time the renewable energy sector is pretty strongly imbued with the entrepreneurial spirit, it’s involved in decreasing our reliance on fragile imported sources of oil, it’s achieved a high degree of support from many of the US military services, perhaps, most emphatically, the US Navy.

It also plays a potentially important role with the advent of electric vehicles. So I mean, there’s a whole bunch of rationales that with the right packaging and the right spokespeople could perhaps be persuasive across the political spectrum. It has not been that effective in the past, but maybe we can learn from that and do something differently [laughs].

But with regard to those concerned about the future of legislation that relates directly to climate change, I’d say this: When people don’t believe that there is a problem, don’t believe that there is actually any climate change occurring, and then their colleagues believe that if there is climate change, it is not related to human activity, and then there’s a final segment that believes, “Yes there is climate change, but it’s part of God’s will to bring to an end this little experiment on Earth and we don’t want to [mess] around with God’s will” … this is not a promising avenue for policy improvement.

Isn’t this frustrating to someone in your position? I mean, that first Earth Day was a long, long time ago. Do you ever sit back and say to yourself, “Isn’t it amazing that all these years later, people still don’t get it?”

Yes. And in fact, in many ways, it goes more deeply that that. From the very beginning, I had kind of celebrated the bringing of science, broadly, and in particular, the introduction of ecology, into public policy, and to have it playing a role alongside economics and finance and the other things that have historically sort of pushed and shoved policy decisions, legislative decisions, judicial decisions and what have you.

And I thought that it was part of just sort of the next opening up of the process that had begun, really, with the emergence from the Dark Ages and into the Enlightenment. And over the last 20 years, generally, and the last dozen years pretty emphatically, there has been a growing segment of the political establishment reflecting attitudes that had been latent for a while and have reared up again in parts of the public; those attitudes. I think can best be described as anti-scientific and an expression of the traditional American anti-intellectualism – a turn against the pointy-headed professors, if you will. Considering that this is a time when the world is facing breathtakingly complicated issues, it’s discouraging to see this evolve.

On the other hand, I’d like to believe that the curve is an upward ascending one, but one that happens to be a squiggly line, and we’re squiggling down right now. But if we’ve got a future, it really depends upon us beginning to pay attention to facts and letting them trump ideologies. At least occasionally.

Well then, how do you get those people who have adopted this anti-intellectual stance to listen?

Well, part of the answer to that is we tend to worry about how you move the population, or a majority of the population to a particular mind-set, where,in fact, what you really need to move is probably something less than that.

This is going to sound cynical, but it’s just realistic, I think that there is a tendency on the part of a vast number of people, when dealing with issues that are fairly complicated, to follow the lead of people who are absolutely confident in themselves and their own views.

That puts people who care about science at a disadvantage because the whole scientific process is built upon scepticism and exceptions and nuances, and it gives just an enormous advantage to a {conservative television and radio host] Glenn Beck or a Sarah Palin or a [Conservative radio host] Rush Limbaugh, who, in extremous, may believe that their views represent divine inspirations. But, if we can begin to have spokespeople who are quite confident in the way that they express themselves, humble in their demeanour – not being people who become a[s bombastic as] Rush Limbaugh – but who speak with what Mark Twain once characterized as “the calm confidence of a Christian holding four aces” [laughs]… I think if we can pull that together, and we have those who have really dug into this issue and have mastered it representing our view to a reasonable fraction of American society, we still might have a chance.

I’d say that there is still 50 percent of the US population that is still sort of still up for grabs, people who are never going to be reading the articles in Science and Nature or the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, but who are willing to listen -- particularly after we see mounting evidence month after month after month of new weather extremes being visited upon us.

Now having said all that – and believing that it’s really important that it happens just as soon as possible – I don’t believe advances in the renewable energy field are utterly dependent upon a broad acceptance of what science has been telling us about climate. There are a huge number of other rationales.

At the time that [President] Jimmy Carter launched the big renewable energy initiatives in 1976 and 1977, there was still a fair amount of broad scepticism within the established scientific community about climate issues, but we nevertheless had a strong set of rationales for renewable energy. The climate argument has grown much stronger with the passage of time, but it certainly isn’t our only argument in favour of renewable energy, and it may not be our most effective argument.

You left the federal government with the change of administrations from Carter to Reagan, and President Reagan famously removed the solar panels that President Carter had placed on the White House roof. Do you think it was that change in mind-set or political will that really put the US so seemingly far behind Germany and Spain and Japan and others when it comes to renewable energy?

Yes, but let me walk you back a little bit. The panels on the White House got a lot of press, but, candidly, they were solar water heaters [laughs], and therefore weren’t a big deal. But what did happen that was of real significance during the Carter Administration was the establishment of the Solar Energy Research Institute, which is now the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

What people don’t remember is that President Carter doubled the budget for renewable energy every year that he was in office. And they had people, including myself, who were strong advocates for renewable energy and leading the effort, and frankly, working to formally establish a goal of getting up a 20 percent goal of the nation’s energy from renewable sources by the year 2000. We actually compiled a detailed, 400-page plan on how to get there, one that laid it all out in great detail and spelled out the steps that you would need to take over the next 20 years. Now, it would have been a moon-shot thing, but it was entirely practicable if we had done it.

With the election of Roland Reagan, they not only didn’t adopt any of the plans that had been promulgated by the Carter Administration, but they did their very best to suppress the publication that had been paid for by taxpayers showing how you’d do it.

At the same time, they did their best to not enforce the laws that had been set up to encourage renewable energy, including provisions of the – now, this gets wonky -- Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act and other stuff that people had worked hard to get set up as part of the proper framework, and they began to make sarcastic, dismissive and hostile comments about renewable energy.

Which no doubt, in and of itself must have slowed the development of renewable energy here…

Well, America’s capital markets have a great many places where they can put money, and if you’ve got the President of the United States evidencing antagonism toward a set of investments, that’s not going to attract much. So what happened was, at the time that Carter left office, the United States led the world in research, development, demonstration, and, I think, in production of essentially every renewable energy resource I can think of -- certainly of solar electricity, wind power, and most of the biomass technologies – I’m not sure I can make the case for geothermal or not, but at that point, geothermal was pretty much small potatoes everywhere and we were at least competitors in that market.

Then [during the Reagan years] we walked from that, and in the field that I’m most strongly personally focused on, solar, it was sort of picked up eight or 10 years later with some enthusiasm by Japan, and for almost the next decade Japan carried it forward. At the same time, in wind, Denmark was leading.

By the time it got to the year 2000 Japan had moved the ball quite a ways up then line, and then the dramatic changes began to come with the feed-in tariffs, first in Germany and then in a great many other countries, including, certainly, Spain, and then South Korea, China and so on. Meanwhile the United States has not really been present at the banquet, although essentially every commercial photovoltaic material now on the market in any meaningful amount was developed in the US with taxpayers dollars – it was a gift to humanity, I guess [laughs].

As a result today, although we do have a couple of companies, First Solar, for inexpensive cells, and Sun Power, for really efficient cells, that are still players, the muscle of the industry is really located abroad.

Now, that was a really long answer to your question. To put it more simply, I’d say yes, the pivotal point was the election of Ronald Reagan, and frankly that came as a surprise to virtually all of us, because when Reagan was a radio commentator immediately before being elected president, he had two or three programs during which he expressed robust enthusiasm for renewable energy – particularly distributed technologies that returned power to community and individuals and left them less dependent on the state and large, faceless corporations. But once elected president, well, let me put it this way: I don’t know who wrote his radio scripts, but they certainly didn’t write his policies [laughs].

To fast-forward a bit, do you think the US has made any significant strides to bouncing back, in terms of renewable, in more recent years?

I wouldn’t say in the intervening years, but I would say in the last couple of years we’ve been coming back, and that’s because a couple of things have happened. One is we’ve got an administration now that while this is not among their top priorities -- it’s not even its top priority in the energy sphere, where it gives at least equal attention to clean coal and to nuclear power as it does efficiency and renewables -- it at least is not antagonistic toward it and it has appointed a Secretary of Energy [Steven Chu] who has a solid scientific background unlike, essentially, every one of his predecessors, and who’s prepared to be broadly supportive.

There was an awful lot of money that flowed into [renewable energy] as part of the economic stimulus program in the US, this is not so much a policy choice as a desire to distribute a whole bunch of purchasing power and some of it went into this field. Had that been spent over four years or had they been given six months to prepare, I think it could have been spent more wisely, but nonetheless it was a big boost.

Second, we now see the military coming into the renewable energy sector pretty strongly and particularly the US Navy, Army and Marines. The Air Force still seems somewhat sceptical about a lot of this stuff, but the other armed services are being supportive of it, and if you’re looking for federal expenditures whether on pilot programs or simply driving up volume purchases and achieving economies of large scale production, the military has a better record of doing that than the US Congress because they make long-term commitments and by-and-large, they honour them. [The military] is the one place in America where you can have a 10 year plan and it actually is a 10 year plan.

And then, finally, the military also has a remarkably good record in basic research, and there are real opportunities in some of these technologies to cultivate superb academic, think tank, and national laboratory research. So that, I think, is proving to be helpful, and again all this has occurred in just the last couple of years.

Right…

And then the final thing, that has nothing to do with government but it’s really important, is that Silicon Valley has awakened to these things.

Now, that’s no particular surprise because its familiar with Silicon [laughs]. But as a result, semiconductor companies are getting involved in things – some of them coming in kind of arrogantly and learning this isn’t as easy as they thought it was going to be. Sun Power itself is now a subsidiary of Cypress Semiconductor, Applied Materials has now jumped into it, and a bunch of companies that have formidable financial and intellectual resources and lots of experience, are now jumping into it and rapidly gearing up to large scale production once they’ve had proofs of concept and demonstration of the market.

I think that is a segment of the American economy that has historically been on the edgiest part of our global competitiveness and to the extent that they get engaged in renewable energy, it has to be a plus, a huge plus.

When people talk about technology transfer here in the US, and particularly about the collaboration between academia and the business world and venture capital, the conversation ultimately turns to the concept of business incubators and having wet lab space and the like. Now, in my experience, I know those kinds of situations exist for technology start-ups. Is there an equivalent – a kind of business incubator – for fledgling solar power or wind power companies here?

I think so. I mean, they needn’t necessarily be in the same industrial park – although there are advantages to that. There certainly is an advantage to having technology clusters, where people can raid one another’s employees and have an ability to achieve important synergies, and better yet, if it’s near one or two or three good research universities, but that is happening in a great many places in the US – certainly in the Research Triangle in North Carolina and along Route 128 [outside of Boston in the US state of Massachusetts and beneficiary of the flow of talent out of Harvard, MIT and the area’s seven other major universities].

And it’s definitely happening in Silicon Valley. And I think there’s a recognition in a number of fields, including the control technologies for smart grids and in energy storage and in pushing for increased efficiencies and lower costs. But I’m not sure whether there is a similar kind of thing or, candidly, similar sorts of opportunities in some of the other renewable fields. Wind is now pushing pretty close to the theoretical limits of what you can do – unless you start putting stuff up in the stratosphere, but I am dubious about those schemes. But I do think here and abroad there is a great deal of attention being paid to innovative, new ideas, many of them, increasingly, being innovative financial ideas and simply the kinds of advantages you get not so much from the incubation of new ideas, but the synergies of putting line after line after line in the same location and driving your costs down rather spectacularly. I think in huge fractions of the world today, renewable energy, without any kind of subsidies, is the most effective way to deliver energy to a population.

Once you’ve got something like that happening and you create that internal demand… the learning curve is a hugely powerful mechanism. As prices go down, further and further, with volume, the transition will happen. I just regret that the transition is happening now rather than having occurred in 1985.

Your reference to the users of energy, the consumer, reminded me of a discussion I recently had with an architect who recently designed a “sustainable” home in Portland, Oregon in the US, and what struck me in speaking with him was how costly, personal solar and geothermal heating remain here – I think he said it cost something like $25,000 to install solar panels on the roof of the home and another, $30,000 to $35,000 to install geothermal heating… although, of course, much of that was the cost of excavation.

There are a number of things behind that. While the cost of panels has been falling fairly precipitously, the price of panels has been going down much more slowly, in part because there has been more demand than supply. So profit ratios have been going up and that’s allowed more investment to be going into new lines, and ultimately, I think, consumers will be able to benefit from that. Particularly if you are buying really small amounts for an individual house, yeah, it’s tough. Second, the balance of systems has not fallen as quickly as the panels have, so we need to be paying more attention of those other elements which are now, often, way too high a fraction of the total cost.

Third, we really haven’t placed enough attention – although we are starting to now – on essentially plug and play systems that you can install really very rapidly; labour costs tend to be higher than they need to be because it’s taking more time than in ought to take to install something that’s effectively just a modular system. It ought to be able to be plugged in.

But I think all of those are just the kinds of things that happen when you introduce anything in a distributed fashion that requires technical assistant. It’s like the early days of the computer when nobody could ever do anything and nobody understood how this operating system really worked, and you’d spend half your time driving from your office to your house to the place in town where the six people who actually sort of understood what this software was all about to try and get you booted up again. We’re passing through that now with renewable energy, in a way.

And if you are doing a utility installation, a large scale installation, at the top of a mall or a hospital or an army barracks, what have you, you can now get some pretty decent deals in terms of price. The nice thing is it’s increasingly being integrated, at least in new construction, with some heroic opportunities to save energy at the same time.

Aren’t you going through something like this yourself right now, with a new building in Seattle, Washington?

We are. We’re putting up a six-story building in Seattle, which is not exactly known as the solar capital of the world, and we will generate as much electricity on an annual basis from photovoltaic panels on our roof and part of our south-facing wall – which is the shortest wall, alas, because of the nature of the site and the building – as a six-story building uses.

Think about it, it’s a six story building, but the roof area is the same as a one-story building. This is kind of tough. But what we’re doing is, by the time it is finished, it will be the most efficient office building in the world at the time that its completed, and it’s a marriage of how do you do the energy supply and how do you do the energy demand and make them come together as an integrated unit. I think more and more people are trying to make that work now.

When will the building be completed?

Probably about March, April or May of next year; It depends upon the rate at which we get permits out of all of the necessary regulatory officials. Because we’re not only doing the solar installation, we’re also harvesting all of the rain that falls on the roof and using it for all the purposes we can inside the building, we’re going to have composting toilets, which are kind of unusual in downtown Seattle, pervious pavement…

One of the interesting things I had not realized is how illegal it is to build a sustainable building. We’ve come upon a number of regulations that make it very difficult to do it and require work; It’s because the whole nation has been run – and mind you, this has not been an unreasonable historic way to do it – with a whole series of prescriptive standards that’s produced some good stuff, like, you can have more glass than a certain amount in a particular climate and it has to face in a particular direction. You need to have a certain kind of insulation and son.

But if you are building a building that’s an integrated unit and you’re using materials that are particularly applied to a particular kind of design and the whole thing comes together meeting what is called the “living building challenge,” none of those prescriptive things make any sense in our building. So we’ve now persuaded the City of Seattle to allow 12 groups – we’ll just be the first to accomplish it – to build buildings that don’t have to follow most of those prescriptive standards, but will in fact performance standards.

And if we can show that these buildings use far less energy and far less water and have far less of an environmental footprint and use far less toxic materials, and recycle materials and use materials from whatever existed on the site ahead of it, all that sort of stuff, that they will at least consider and, I suspect, actually adopt, a uniform performance based set of standards going forward.

Do these concepts that you’re working with fall outside the traditional LEED, Green Building Council idea of a sustainable building?

Well, it was come up with by some people who have an affiliation – although it’s an occasionally strained and somewhat tenuous relationship -- with the US Green Building Council. It’s called the Cascadia Chapter of the US Green Building Council and of the Canadian Green Building Council. They’ve designed this “living building challenge” and they are smart people. But unlike LEED, which like most existing building codes, requires that in order to get points from them you have to do this and you have to do that and the next thing, you have to use this material and your building has to have that orientation, and you get a certain number of points for having solar panels and for employing bicycle racks.

And LEED, basically by the time you sign off on your architectural drawings, as long as you fulfill it, you know whether you are going to be LEED gold, LEED silver or LEED platinum because you know you’ve checked all the relevant boxes and you just have to build it. That has been a huge beneficial thing for American architecture and developers and the building industry in general.

When you look at studies of how these buildings perform, you find that on average Gold buildings are better silver buildings and platinum buildings are better than gold buildings,. But those averages also hide some things, and if you look at the very best silver buildings, they can be significantly better than many of the platinum buildings, because the buildings don’t perform as well, whether through errors in the construction process or some things got fudged or they are not operating the building correctly.

So what you do with the living building challenge is, when you finish your architectural drawings, you don’t get anything, when you finish construction you don’t get anything, you have to have operated the entire building for at least one year continuously and met the standards they were set out before you know whether you have succeeded or not. It’s all based on how the building performs.

To get back to renewable energy, I know you’ve been heavily involved in solar for most of your adult life, to what extent have you been involved with wind and other renewable?

Well, back when I was running the Solar Energy Research Institute we ran an innovative wind program for the US Dept. of Energy, I’ve always been very enthusiastic about wind and I think it can be a very significant contributor to the world’s energy budget. But its potential is probably akin to the amount of energy that we currently get from natural gas, and that’s huge, but the potential for solar is a very, very high multiple of al of the energy we get from all sources. And solar you can put in a distributed fashion on the rooftops of buildings like mine so it integrates much more easily with the grid, you don’t have the transmission losses, the transmission difficulties – of course, you do from centralized solar sources, but it has a variety of different ways that you can integrate it into life.

So if you are trying to build a human environment that is based upon the principles of ecology – and in basic ecology, energy is the currency -- all of it comes from the sun … with the exception of a few microbes that live around geothermal fonts down at the bottom of the ocean. So for all intents and purposes, if you are trying to emulate what nature does with every other species on the planet -- and did for a very long time with human beings as well prior to coal coming into play a pretty important role after James Watkins steam engine took gear – the answer has to be solar. We’ve just sort of left that whole course, and had an abundance of really cheap, really abundant energy, unlike all of the rest of creation, and now that there are serious constraints being applied to that cheap, abundant, but highly polluting and politically consequential set of energy sources.

My thought is that we ought to go back and learn from all of the beta testing that nature has been doing for the last couple of billion years. And that suggests that if we can use solar to meet human purposes, there are some huge advantages to it.

And finally the creativity of the human mind, when applied to that, allows us to stand on the shoulders of nature and in fact go one better, in that nature produces almost all of its energy through photosynthesis, which is an astonishing wonderful process, but not super efficient.

The waves that are able to be absorbed represent maybe half a percent of all the energy that falls on the planet gets converted into some kind of energy. With good photovoltaics, a really good one, you’re well over 20 percent. And then the theoretical efficiencies go dramatically higher: Some of the experimental cells or the space applications, super expensive concentrating cells and what have you. It just has an intuitive appeal to me and has since the early 1970s as the obvious solution. In fact, I actually jumped on it as the issue I was going to be principally focusing on because it seemed so intuitive obvious and logical that I thought this would be a really easy one to deal with instead of getting into the really tough issues like population growth or something [laughs]. I thought, “Of course we’re going to do this one.” And hopefully, before I die, we will.

For additional information: